Sofia Aldinio

Visual Journalist + Storyteller

In 2016, I was sitting in the living of my new friends, in Portland, Maine. It was late, the party goers spirits were changing while more states were turned red. I witness my friends holding each other crying for the uncertain future her trans daughter will hold. I started fearing about my own future. What would happen if my status of being a resident was going to change, meaning that I had to leave my son and husband behind. I started fearing about my immigrants friends, some undocumented, some on asylum status and all the refugees on my community. At 3 am, by myself, with my laptop in bed, I watched with tears of uncertainty how Trump celebrated with his supporters and became the 45 president elected in the United States.

I left Argentina by choice, carrying an unresolved trauma, something that I felt related to the immigrant community living in Portland, Maine. The latino community in Maine it’s small, making it 1.8 percent of the population, data from the U.S. Census Bureau, putting me in the minority and harder to find a community to feel related to. After opening myself to the African and middle east community I found that cultural barriers were broken when we opened up and shared our own personal story.

The migrants have been arriving in Portland, Maine, by the dozens. The surge has opened a debate in the city, which needs new residents but also has filled its shelters. Portland has become a focal point for a sudden surge of migrants, who are seeking asylum.

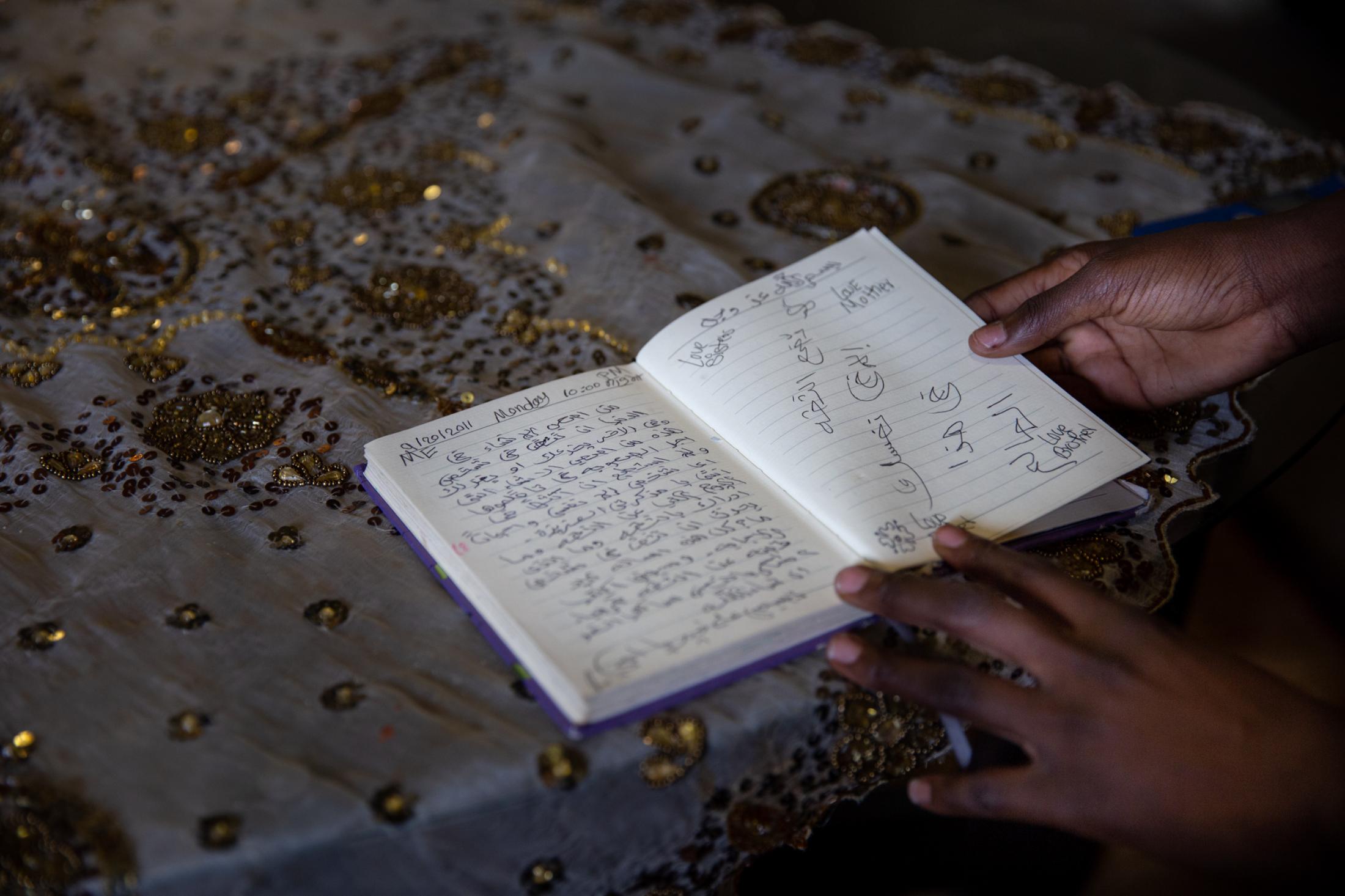

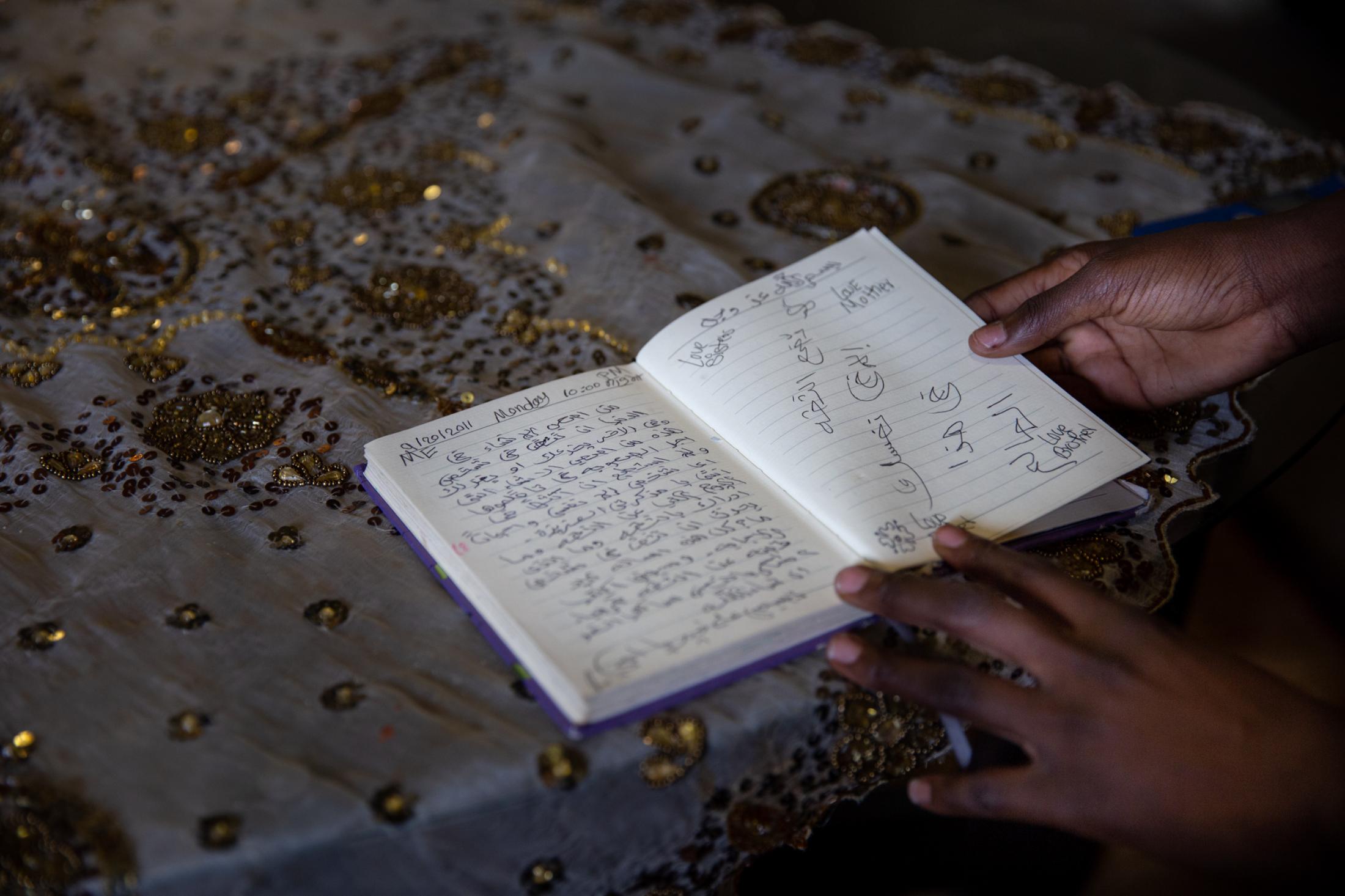

In 2018, the Maine Art commission granted me money to create a travel exhibit that will help people born and raised in Maine understand why their city, Portland Maine, was rising with immigrants mainly from Africa and the Middle East. I did this creating a space where immigrants could share their stories and displaying objects that they brought from their home country.

In 2020 with the hope that my work once will become a document for research of the immigrant community in Maine, I went to the street hoping to take a step back and let the community speak. I was curious, and instead of asking questions, I let them guide me to the questions. I found a similarity in the way they were living. Once you step inside their homes, you are transported to a new continent, depending on the nationality. I learned about their stories and trauma, and the hope to belong, that’s where the name was born. When interviewing these individuals there is often a longing for their birthplace and culture overlaid by a humble acceptance of the daily struggles gifted by the security of a small city in Maine.

Belonging was born as a collaboration, of what they shared and my perception as an immigrant, seeking to highlight the often cloudy memories of trauma along with a culture left behind that each of my subjects grapples with while establishing a new sense of meaning inside a novel community. The project is a visual combination of the silent trauma immigrants and refugees face through both their reflections upon fleeing their cultural roots and the stark differences seen and felt inside an urban community within one of the most white states in the country - Maine.

Working together with organizations and individuals fighting for immigrants rights in Maine, I was able to collaborate with them to raise their voices. The intent of this project is to deepen the understanding of the passages of the refugee and immigrant communities, inviting us all to reflect upon how we are receiving these people, to question if we can empathetically understand what they’ve been through and to ask ourselves what we are doing to create equitable spaces for these individuals and groups to reveal their gifts within our society.

In 2016, I was sitting in the living of my new friends, in Portland, Maine. It was late, the party goers spirits were changing while more states were turned red. I witness my friends holding each other crying for the uncertain future her trans daughter will hold. I started fearing about my own future. What would happen if my status of being a resident was going to change, meaning that I had to leave my son and husband behind. I started fearing about my immigrants friends, some undocumented, some on asylum status and all the refugees on my community. At 3 am, by myself, with my laptop in bed, I watched with tears of uncertainty how Trump celebrated with his supporters and became the 45 president elected in the United States.

I left Argentina by choice, carrying an unresolved trauma, something that I felt related to the immigrant community living in Portland, Maine. The latino community in Maine it’s small, making it 1.8 percent of the population, data from the U.S. Census Bureau, putting me in the minority and harder to find a community to feel related to. After opening myself to the African and middle east community I found that cultural barriers were broken when we opened up and shared our own personal story.

The migrants have been arriving in Portland, Maine, by the dozens. The surge has opened a debate in the city, which needs new residents but also has filled its shelters. Portland has become a focal point for a sudden surge of migrants, who are seeking asylum.

In 2018, the Maine Art commission granted me money to create a travel exhibit that will help people born and raised in Maine understand why their city, Portland Maine, was rising with immigrants mainly from Africa and the Middle East. I did this creating a space where immigrants could share their stories and displaying objects that they brought from their home country.

In 2020 with the hope that my work once will become a document for research of the immigrant community in Maine, I went to the street hoping to take a step back and let the community speak. I was curious, and instead of asking questions, I let them guide me to the questions. I found a similarity in the way they were living. Once you step inside their homes, you are transported to a new continent, depending on the nationality. I learned about their stories and trauma, and the hope to belong, that’s where the name was born. When interviewing these individuals there is often a longing for their birthplace and culture overlaid by a humble acceptance of the daily struggles gifted by the security of a small city in Maine.

Belonging was born as a collaboration, of what they shared and my perception as an immigrant, seeking to highlight the often cloudy memories of trauma along with a culture left behind that each of my subjects grapples with while establishing a new sense of meaning inside a novel community. The project is a visual combination of the silent trauma immigrants and refugees face through both their reflections upon fleeing their cultural roots and the stark differences seen and felt inside an urban community within one of the most white states in the country - Maine.

Working together with organizations and individuals fighting for immigrants rights in Maine, I was able to collaborate with them to raise their voices. The intent of this project is to deepen the understanding of the passages of the refugee and immigrant communities, inviting us all to reflect upon how we are receiving these people, to question if we can empathetically understand what they’ve been through and to ask ourselves what we are doing to create equitable spaces for these individuals and groups to reveal their gifts within our society.