Sofia Aldinio

Visual Journalist + Storyteller

CARRIED FROM HOME

The stories of ten refugees living in Maine and the treasured possessions they carried with them.

Through these objects, and the stories of those who behold them, we explore the malleable concept of value as it relates to who we are, what we own, where we call home, how we raise our families, what matters most in our lives, and the values we share as cultures collide and coexist in our state. New Mainers are binding the fabric of our local economies and weaving beautiful social constructs within our communities. These are the stories of those who are building new lives, and bolstering our state in the process. By bringing these stories to light, and creating a platform for community engagement, we seek to celebrate the changing face of Maine and promote greater understanding and integration.

The project tells 10 stories of refugees living in Maine visually connected by the treasured objects they carried, and each story narratively linked through the exploration of the central theme: value. The project culminated in a travel exhibition featuring images, artifacts, and editorial from the project, along with the subjects themselves.

This project was funded by The Maine Art Commission, with the support of the City of Portland, Venn & Maker, American Roots and many other community members.

Abdi Iftin

Abdi Iftin is from Somalia. Before he arrived in Boston by way of Kenya three years ago, he had never thought of himself as a person of color. “ I have dark skin. Everybody I knew looked like me. No one ever called me black.” He refers to his first experience in America as “extraordinarily weird.” Upon landing at Logan Airport, he completed a form identifying himself by race and color.

Abdi was six in 1991 when Somalia erupted into Civil war and “everything fell apart.” He describes a horrific scene in which Mogadishu was leveled as warlords battled for control. The militias were eventually ousted, but a new moral code was imposed. Sharia Law forbade Western ideology. “No soccer, no movies, no music, no dancing, no girlfriend, nothing.” Abdi feared Al-Qaeda recruitment and decided to run. “I never thought that I would leave behind my family, my city. We ate some days, we didn’t eat some days, and that was life, and we got used to it and we were surviving and growing up.”

There was no formal school in the burned out city, but Abdi had learned English at the movies. He crossed the border into Kenya to join his brother who had left nine years prior. But Kenya was not safe. Kenya sent troops to Somalia to fight the Islamist state. In retaliation, Al-Qaeda unleashed terrorist attacks on Kenya. So Kenya turned on its Somali refugees with threat of imprisonment or starvation. Abdi applied for the lottery to gain amnesty in the United States. He won. Abdi speaks frankly about the trauma he carries. In Maine he feels safe, but there are challenges. “There’s the nightmares every night where you think about your mom, I think about my brother.” Abdi left Kenya empty-handed. “I didn’t have a watch, necklace or anything that I could bring as a memory, but everything is pictured in my head.” When he talks about his childhood he says, “I miss seeing my mother’s face.” He languishes over they way she smelled after traditional gatherings. “[The women] read blessings, then they smear themselves with really nice-smelling perfume, and when she comes home that’s the smell that can never get away from me. Almost 8 years I have not smelled it. If I smelled it again it would connect me.”

Nothing can keep his family safe, but at least Abdi can save them from starvation by sending money. He would like to sponsor his mother to come to Maine but she’s getting older and wouldn’t like the cold. He wants her to see that it’s safe. Most emphatically, he wants to take her shopping at Hannaford's. “Mom, see they have mango! They have banana!” He would visit Somalia if it were safe “but I have to come back because, to me, America is home.”

Abdi mapped his own path to Maine. A natural storyteller, he reported from the frontlines of the war in Somalia using his cellphone to file daily reports with a radio station in North Carolina. A family in Yarmouth Maine was listening. Captivated, they began an email correspondence. They met Abdi at Logan Airport and brought him to their home, where he still lives. Finding inspiration in their tranquil backyard abbutting the Royal River, Abdi recently completed his memoir. “It’s gorgeous,” he says. “A quiet place to sit and think.” Abdi’s book, Call Me American: A Memoir will be available from Penguin Random House on June 19, 2018.

African Dundada

African Dundada is not his given name, but it is the name that gave him purpose and redefined him as an artist. Born, Mark Otin, and known by his initials, M.O., he started to build a name as a rapper, but struggled to find a deeper purpose to his music. Something shifted when he changed his name and focused on inspiring others. Dundada means “Big Deal,” and he doesn’t bear the name lightly. He feels like “one of the luckiest people alive” because he came to America as a child. “Where I came from, there’s kids who don’t go to school because they can’t afford it or school is too far. To get there they have to walk from night to day.” He wants to give voice to those who didn’t make it out.

African was born in South Sudan mere days before the country erupted in civil war. He spent the first 10 years of his life in Uganda, first in a refugee camp, and then in a remote village. He remembers fields full of deadly snakes, and how he and his siblings would tie plastic bags on their bare feet in the heavy rains. He can still smell the air and the food cooking. It was the smell of survival. “We used to shoot a bird, make a fire, fry it up. Your parents could disappear for a week and you knew how to survive. We eat to make it to the next day”

His family never decided to leave Sudan. “We just had to get up and go. I remember hearing stories from my parents. They saw people falling, just getting shot like animals.” African didn’t witness those atrocities but he feels the acute loss of his South Sudanese identity. “I’m like a ghost in this world. We didn’t have birth certificates, photos. It’s like what happened to us never happened.” He exudes such reverence for his family’s plight, it is as though he could develop the negatives of his ancestors’ memories. Through music, African can document life. He wants to see more traditional African rhythms represented in today’s music and he brings that to his craft. He has never recorded in a professional studio: everything about African is self-made.

African was ten years-old when he moved to Maine with his parents and siblings. Of Portland he says, “It’s small enough you can get a piece of it, and at the same time you can build something from scratch.” This viewpoint is retrospective. African left for five years to chase success and spent two years homeless. Now, he is back on his feet and feels focused. “Maine is where I started. If I can’t make it here. where am I going to make it.?” He says Portland “is the most diverse place I’ve ever been. It’s the only place that accepts me for the immigrant I am.”

African is shaken by the rash of school shootings in America. He hopes “Maine’s diverse little bubble” will provide a safeguard against similar tragedies. Mostly he wants people to know that he’s approachable. “I care about the world; I care about people.” His father, a lifelong diabetic, is unwell. With his grandparents ailing too, African’s support system is fragile. He feels a sense of urgency to succeed. “I can’t just say I’m a musician. My music has to be more powerful.” When African performs, he wears a shirt made from traditional African fabric so his grandmother will recognize it in his videos. Of embracing culture, African says, “This world is a beautiful place, but with so much misunderstanding, we lose the most important parts of ourselves. I’m just happy I get to wear this shirt, and that I get to say I’m African Dundada.”

Akad Al Hilween

For Akad Al Hilween, the choice to leave Baghdad was not simple. An artist and a philosopher by nature, Akad speaks of Baghdad as his muse. He describes a maternal relationship between Baghdad and her citizens. “It’s a very old city. She’s like mom, like home. It’s not just a place.” But Iraq was changing. The extremist group, ISIS had taken over the north of Iraq, and Akad sensed a shifting moral code in his beloved city. He no longer trusted in the goodness of his fellow Iraqis. Akad and his wife and son were no longer safe. For two months he agonized about the decision to leave. But when he finally made the difficult call, he didn’t equivocate.

Akad and his family spent two months in Virginia before moving to Maine. All they knew of Maine was its proximity to the ocean, and that there would be some snow. “Snow sticks eight months here. It was nice at first, but after that, it’s too much!” Akad echoes the sentiments of even the most seasoned Mainers after a treacherous winter. While many immigrants move to Maine to connect with a large diaspora, or to access its renowned refugee resources and services, Akad was drawn to MECA: Maine College of Art.

It has been two years, and the pace of life is still a shock. “It’s busier here. Everyone’s always busy. In Iraq, you could spend time in conversation, talking about life and art. Here if you’re having a conversation, you’re always talking about something like DHS.” Although there is a significant Iraqi population in Portland, Akad mostly keeps to himself. “There’s no problem with them,” he clarifies, “but my thoughts are different. I think a lot about art about humanity.” Akad is desperate to share his perspective with the world and create something new. He loves music, and plays a bit of guitar, but he doesn’t have the time to commit to honing the craft. For now, he chooses to focus on his painting.

In Iraq, Akad was an art teacher, with a strong command of language. Now, he says, he has many stories to tell, but he isn’t ready for that yet. He feels barricaded by the language barrier. “When you say something in English, it is hard to say what you feel, so by art, music, painting, that’s easier for people to understand.” Akad thinks about his past like a book. “I open it just to see something and then put it back in my library.” It’s too painful to think about his past. “In the future, I’ll look at the book, and maybe paint, but not now. It doesn’t matter. I’m safe now.”

For Akad, Baghdad is home. He dreams of someday helping to build a new Iraq, founded on pacifist ideals. When he moved to the United States, the hardest possession to leave behind was his collection of art books. He disbursed them among his friends. He shrugs, uncertain about whether his friends have kept them. He did manage to bring a few books with him, and they travel with him everywhere. He says that the smell of natural earth and fire smoke are his most evocative aromas, but I imagine the scent of these books conjures even more.

Anaam Jabbar

The first thing Anaam Jabbar wants you to know about her is that she is an educated woman. She studied to be an agricultural engineer, but her degree isn’t recognized in America. Instead, Anaam sews for American Roots, a made and sourced in the USA fleece-wear factory, where she is head of the labor union. She’s vastly overqualified, but she is grateful to be a part of a small enterprise where, “they treat us like family. You feel human.”

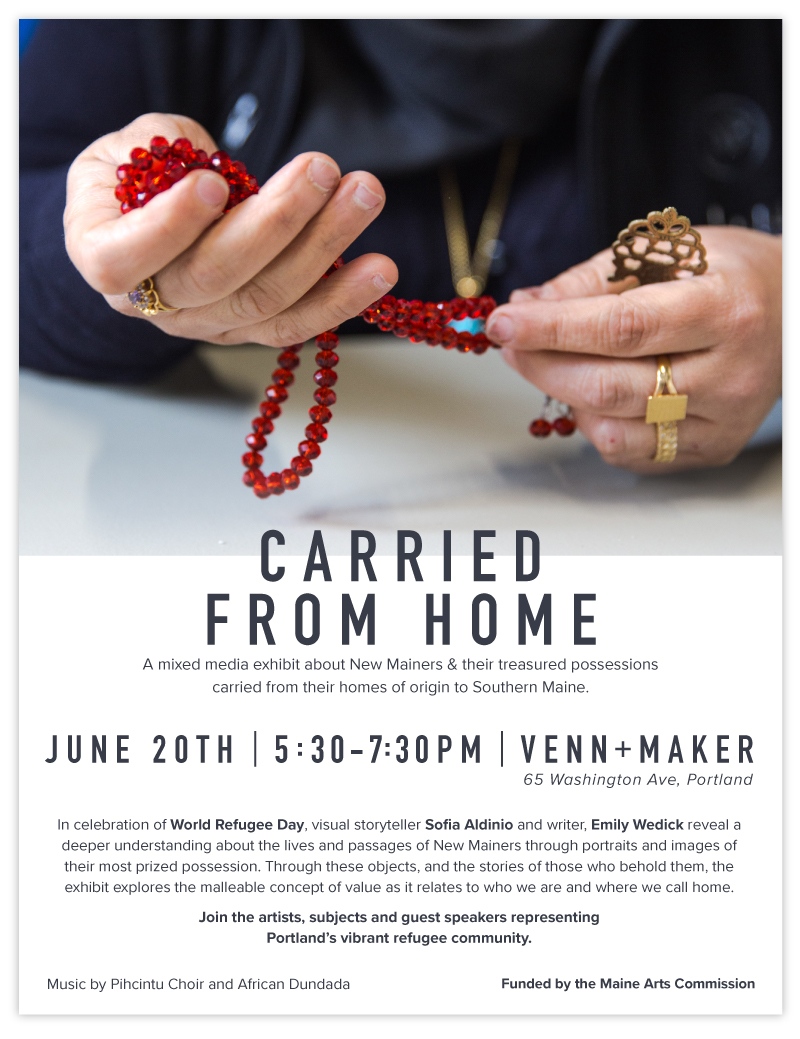

In the break room at the factory, Anaam sets two objects on the table. One is a delicate golden urn, not much larger than a key, with an intricate, latticed, wafer-thin top connected to a narrow pestle. The object, called mekhala, in Arabic, is the container that holds a fine black powder ground from fig seeds. “This is famous in my country,” Anaam beams. “We have people from Iraq who make this.” Women mix this powder with water to make a thick black eyeliner. “All natural,” Anaam touts, stating its beneficial qualities for sensitive skin. But carrying this mekhala is less about the magical properties of the beauty product it holds, and more about a reverence toward tradition. It was handed down from her grandmother, to her mother, to Anaam.

Anaam’s stunning, hazel-green eyes are impeccably lined. These days, she orders the powder from abroad. The other item is a necklace, strung with luminous, red, jewel-shaped glass beads. Anaam snakes it through her fingers and lays it gently across her palm. It was her mother’s necklace. She wore it to give her strength, and Anaam has done the same.

Now, having carried it over 5,500 miles to her new home in Portland, Maine, this treasure is Anaam’s connection to her newly widowed mother in Baghdad. Sure, they can chat over Skype, but there are memories housed in our heirlooms that aren’t always as easily accessed through a video screen. It is the love of her family and ancestry that she carries as one of the new faces of Portland, Maine.

Brenda JoJo Violer

Brenda JoJo Violer is from South Sudan, but she doesn’t remember it. She was two years-old and tied to her mother’s back when they fled to a refugee camp in Kenya to escape civil war. With no photographs, Brenda doesn’t know what her relatives look like. “That’s a really sad part of my story. I’m always trying to find who I am. It’s hard for me when I say I’m from South Sudan. People ask, what place? And it’s just too painful for me that I don’t know.” Brenda’s father helped them escape. They never saw him again. They believe he would come looking for them if he were alive but they refer to him as lost.

The value of a landing place can be measured in safety. Kenya was safe from the war, but people in the camps were starving to death. “You see young kids just die in front of your eyes. That’s why ever since coming here, it’s like Hallelujah! It’s a miracle for me. I never felt safe before like I do now.” It took eight years to leave the camp. Brenda’s best friend left the same day. They cried together in the airport. They were not allowed to carry much, but Brenda held onto a rhino horn momento from her friend. “When you are a teenager, your friends are everything.”

This spring, Brenda will graduate from Deering High, a school that made headlines as the first in the nation to provide athletic hijabs to female Muslim athletes. Brenda is not Muslim, but the story reflects her experience. “We call it the One School. We respect people from different cultures.” She has good friends and surmounted vast language barriers. It is an incredible accomplishment for a young woman who rarely attended school in Kenya. Brenda takes classes at Maine Medical and aspires to be a doctor or nurse. She has been accepted at several colleges and is still deciding, but one thing is certain: she wants to stay in Maine.

Brenda’s mother is getting ready for church and is embarrassed about being photographed. She returns in a fresh outfit and poses with her daughter. She returns again, this time in traditional African dress. She confesses that her previous outfit was for the photo shoot. Susan tries to keep culture alive for her children. “She writes songs. Everything in real life we make into song. That’s how I learned about my culture, how I became a singer too.” Brenda is a member of the Pihcintu Multicultural Chorus, a group of refugee girls who have performed their music and stories on high profile stages including the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C.

Susan is on disability, suffering permanent damage from a broken collarbone. There was a car accident on the way to Kenya. Brenda’s injuries were only cosmetic.“I got a big scar on my head. That’s why I always wear this.” She points to her purple headscarf. In order to pay for the internet, Brenda works for Cultivating Community, an organization that expands food access to New Mainers through sustainable farming and school nutrition programs. “I’m passionate about helping people. That’s my thing.” Out on the farms, Brenda loves the smell of trees. “In the refugee camp we had a lot of trees.” “I smell the freshness and that makes me happy.”

Immaculee Basiluaeu Ntutu

Immaculee Basiluaeu Ntutu, with her husband, Vincent, and their three children, arrived in America from the Democratic Republic of Congo in May 2016. They landed in Arizona and boarded a flight to Boston one week later. They could not pay the checked baggage fees required for the last leg of the achingly long journey, so they left behind a bag of their daughters’ possessions. Though it upset them at the time, Immaculee laughs about it now. It is not the bag that required safe-haven. They continued on by bus to Portland, Maine.

In Arizona, a state that receives one of the largest percentages of refugees in the nation, someone assured Vincent that, “Maine is a good place for new people coming to America.” For Immaculee’s family, it was. Shortly after arriving, she discovered a cousin living in Portland. It is an astonishing coincidence, although Immaculee is not the only person to tell the story of an unexpected reunion. While Maine received less than half of one percent of all refugee arrivals in 2017, refugees making a second migration to Maine is a common thread.

Of her new home, Immaculee says, “I like the neighborhood and people in Maine are very kind.” Immaculee speaks joyfully, stopping frequently to coo at her two year-old son, Yohan. In Congo, Immaculee bought bracelets with each family member’s name spelled out in alphabetic beads. Yohan’s is his only momento from a country he escaped as a newborn. Immaculee dons one too, but her most sacred possession is her bible. It is bound in worn, butterscotch leather, a fitting symbol for her enduring faith.

There is an ebullience about Immaculee that buffers the world from her struggles, and from the instability she fled. In Congo, Vincent participated in opposition party protests against the brutally violent government. This endangered their family. While the country is a Democratic Republic, Immaculee jokes, “I can say democracy is only a name.” In the United States, they are free to criticize the ruling government. Back home, such subordination is a death sentence. “In Congo,” she says, “there is no safe place.”

Although they arrived only two years ago, Immaculee reflects on their early days as though it has been much longer: a testament to how quickly she has adapted. “At the beginning, it was difficult, because you left everything when you came here. You have to walk even if it’s very cold. You don’t know English. Yes, the beginning was difficult. But now it’s ok. Now I can say I feel good in America. I’m integrated. We can even find Congolese food.” The smell of Congolese cooking brings her back home. In her Portland kitchen, she makes traditional meals from beans, cassava leaves, and salted fish. She laments that her children don’t like it. Like most young children in America, they prefer pizza and cereal.

Immaculee misses her extended family, but she does not expect to return amidst the continued violence. She and her husband grew up in Kinshasa, a large city she compares to Washington D.C. They spent nine years in Lubumbashi, a city rich with cultural landmarks and tourist attractions. She studied there but her degree does not translate in America. Immaculee dreams of studying communications and journalism in Maine. For now, she is raising her children, their names spelled out on bracelets from a country that they no longer call home.

Martine Mathant

Martine Mathant, 46 years old, is from the Democratic Republic of Congo. She came to the United States via Johannesburg, South Africa, where she fled with her children to escape the violence raging in Congo. She had a good job as an assistant human resources manager, until life shifted in Johannesburg. Anger toward refugees seeking South African jobs was mounting into violent xenophobia. It is visibly difficult for Martine to speak about the details of her experience. Recounting a painful past can be retraumatizing. What is clear is that Martine needed to go and she didn’t have much time to organize a plan.

A childhood friend from Congo now living in Washington D.C. urged Martine to join him. Martine left her children with her sister and flew to America, her friend’s phone number her only lifeline. She landed in Atlanta and tried to call her friend while she waited for her connecting flight to D.C., but his phone was off. “I was trying and trying and he didn’t pick up. I cried” A Kenyan pastor she met on the plane took her in while she attempted to contact her friend, but after three days, It was clear that he was off the radar. She was alone. The pastor bought her a Greyhound bus ticket and told her to go to Maine where she could find social assistance. When she finally arrived in Portland, she hitched a ride to a shelter and began to assemble a new life in a place much different than she had expected. She never reached her friend in Washington D.C. again. It is unsettling, but solving that mystery can’t be a priority now. Martine is focused on survival.

In only two years, Martine, who spoke only Swahili when she arrived, has adjusted to life in Maine. “Where you find yourself safe and welcome, that’s where you feel you are home.” She is outraged by the inequity, rape and violence suffered by women in Congo. Being recognized for her full human potential is her deepest desire. She recognizes that the cards are stacked against her as an African woman and a refugee. “To be considered despite my skin, despite my way of talking, I want people to see like I can do whatever a human being can do.” In Maine, she feels seen. Martine believes that without the assistance she received from the state, she would be on the street. Instead, she attended a program that teaches newcomers how to seek asylum, food, shelter and clothing. “They teach us everything about how to look for a job after school. They are teaching us English and computer skills.” She is building the capacity to thrive.

Now Martine lives in Westbrook with Congolese roommates, and enjoys the comfort of speaking Swahili at home. Describing the aroma of her favorite traditional meal of fufu (a cornmeal porridge most closely compared to grits) with fish, she breaks into a rare smile. Although many of her memories of Congo are marred by tough events, it is still her place of origin. Martine places a bag on the table and removes swaths of African fabric called kitenge. Embellished with shimmering beads, the pieces form a top, a wrap skirt, and a headscarf. “ It’s the thing that I took to remind me of where I came from.” It was a gift from her sister-in-law who has since passed away. “This cloth is so attached to me, if I see it I see the love of my sister-in-law.” Martine says, “If I wear this, I feel that I am an African.” It is a prideful statement. Like countless other refugees, Martine came to Maine seeking nothing more than a safe reception. But through a combination of opportunity and her own steely perseverance, she was able to chase down a sense of dignity in the process.

Nahla Ghanwan and Khalid Alkinani

Nahla Ghanwan and Khalid Alkinani, with their son and three daughters, left Iraq and began their American journey in Reston, a Northern Virginia suburb of Washington D.C. The cost of living was prohibitive and violence plagued the schools. A teacher warned Khalid to take precautions with his beautiful eldest daughter, intimating that the boys were not to be trusted. In Iraq, they had lived in a luxurious home. In Reston, Khalid’s salary didn’t even pay the rent and the children felt terrorized at school. They came to America in the name of safety.

Khalid does most of the talking. His English is stronger than Nahla’s, but her comprehension is solid. They tell their story with with the ease of any long-married couple. “Community is really a big thing in Iraq. If you cook a meal, you’re gonna eat five different meals the same day because everybody is gonna knock your door to give you what he cooked.” In Westbrook, Maine, they introduced this tradition to their neighbors. They arrived in Maine five years ago. Khalid jokes that they are still freshmen, but in a state that considers a person to be “from away” if their parents were born in Massachusetts, what they have achieved is remarkable. While we are talking, a neighbor stops by to borrow their minivan. Nahla and Khalid have created community.

In just four years, their eldest daughter, who spoke no English when they arrived, received a full scholarship to college. Their son, Mohammed is a ranked mixed martial arts (MMA) fighter, and college student. Nahla and Khalid left Iraq to save their children. That their kids are now flourishing justifies the struggle. Nahla used to teach. In Maine, she worked at an Arabic store and had a seasonal job at Macy’s. Then she met Ben and Whitney, owners of American Roots, a company that ethically manufactures fleece products in Maine. The company employs dozens of resettled refugees, mainly women. It’s where we first met Nahla. Khalid manages a gas station and store. He likes the owners and feels trusted. In Baghdad, Khalid ran a catering company and other enterprises in the market, where he says he knew everyone. “But I’m just a stranger here. It’s hard to start business, so this is my work.”

It is winter and Nahla and Khalid are remembering the rose bushes in their garden in Iraq. It was delightful to sit there in the evenings and drink tea with friends. “It’s in my nose,” Khlalid says of the garden. We talk about how smell is a powerful link to our memories. Nahla most loved the scent of the orange trees; she used to make fresh orange juice and jam. Khalid remembers the smell of dust after rain. He takes a moment here. Nahla explains, “it’s difficult for him.” He continues, “there’s a special smell when it's raining. It’s the smell of home.” I ask if they are home in Maine. Nahla says it is home for their kids. Khalid explains the duplicity of loving two homes, likening Iraq to his mother, and America, to his beautiful wife.

Nahla misses her mother. She shows us the vibrant blue prayer beads her mother gave her. Running her hands over the smooth beads is calming. Her mother also sewed a beautiful wall hanging with fine golden and silvery threads. There is a pocket to hold the Koran, their holy book, but inside Nahla also keeps a picture of her parents. They are waiting for their citizenship and cannot leave the country until they receive it. When that happens, Nahla will return home to see her family. I ask if the wait times are longer in the current political context. Khalid just smiles. “We are waiting,” he says.

Parivash Rohani

Parivash Rohani is from Iran. Her identity is strongly tied to the Baha’i faith. Iran, an Islamic state, is both the birthplace of Baha’i and the epicenter of persecution against it. Raised Baha’i, Parivash couldn’t understand why she was harassed at school when she looked and spoke like the other children. After Iran’s revolution in 1979, classroom bullying escalated into imprisonment and execution. It was now dangerous to be Baha’i.

One morning, Parivash’s father received a warning that Bahai homes were being burned. Parivash was sent to stay with a cousin at the university, and by evening, their home was destroyed. Parivash was stunned. The sole possession she carried was a necklace given to her by her mother when she turned fifteen. It had once been her grandmother’s, and she wore it faithfully around her neck. Part of a protection prayer is inscribed on it in Arabic and today, Parivash keeps a sheet with the Persian translation.

Parivash’s uncle built their home the same year it burned down. It was large and full of furniture. Now, everything was gone. A known Baha’i activist, It was time for Parivash to leave too. Hoping to return to Iran, she sought refuge close to home, and went with two cousins to Southern India. Stifled by the heat, the Iranian cousins cut off their long hair, only to learn that women with short hair were viewed in India as suspect. Indian women wore Saris that revealed their stomachs. This was forbidden in Iran, but it was too hot to be fully covered. “So we decided to wear Saris. And that made our life so much easier. I still was Parivash Rohani with the same values. I just made the choice to wear different clothes.” She acknowledges that adaptation is an individual decision, but she ascribes strongly to the “When in Rome” mentality.

Parivash met her husband in India and they left for California in ‘85. There, the Iranian diaspora was so large, they struggled to integrate into an America beyond it. They heard rumors of a state that was frozen, wild, and remote, and in the Winter of ‘86, they landed in Maine. “It was beautiful. Really it is the way life should be!” Parivash laughs heartily, but the early days were lonely when neighbors sheltered inside. Desperate to make connections, Parivash decided to bring food to her neighbor. The neighbor later told Parivash that when she heard her new neighbors were from Iran, she was scared that “a bunch of terrorists” had moved in. Now, Parivash is the school’s emergency contact for that same neighbor’s children.

Parivash loves to assimilate, but some traditions are firmly tethered, like rosewater. ”When somebody dies, they pour rosewater in people’s hands. All of these significant occasions are mixed with the smell of rosewater, so it takes me back to so many memories.” She once baked a rosewater dessert for a potluck at the YMCA. She gleaned from the “disgusted faces” that rosewater is an acquired taste. She finds humor in this. Her humility is disarming. An (now retired)ICU nurse in Lewiston, Parivash was able to connect with patients and their families in a way that she believes promoted healing beyond the basic practice of medicine. Her patients nurtured her, as well. “Really connecting with people energizes me.” Parivash is an advocate for Baha’i human rights worldwide, and hosts screenings of the documentary film, “To Light a Candle” by Maziar Bahari, as part of the Education is Not a Crime campaign.

Suzan Ali

Suzan Ali was born in Sudan. She lived in the capital city of Khartoum until she was nine years old, long enough to hold onto formative memories. But civil unrest was mounting in the country. Food insecurity plagued the city, and her parents decided it was time to leave. They went to Egypt, where they would stay for six years, striving to go to the United States.

Suzan’s mother was a midwife in Sudan. Then, in Egypt, she had an accident that rendered her disabled and changed the family’s fate. She fell and broke her wrist. The family suspected something was wrong when she went in for a routine two-hour surgery, and emerged eight-hours later. A criminal surgeon allegedly removed her hip bone and transplanted it into her wrist, but it was revealed that he stole the hipbone for nefarious purposes, and implanted a needle into her wrist instead. She was slated for emergency surgery and sent to America.

Suzan was fifteen when they arrived in Maine, a place she describes as “very cold.” She had expected all of America to look like New York City. It has been nine years, and Suzan is 24. She looks back on immigrating as a teenager, and says it was tough. She is very close with her mother. “We always make sure if anything is wrong, we tell one another. That’s how we can keep up with our traditions and where we came from, even though it's a new place, new people, new language.” Suzan lives at home with her parents and one of her sisters. They have a brother too, but he remains in Egypt. The family has tried, unsuccessfully, to bring him to Maine.

“Now that I’m here in Maine, I don’t think I’d be able to live in a different state. Maine is safe.” Most people have been friendly, but Suzan misses the communal lifestyle of Sudan. Of her neighbors here she says, “I don’t know their names. If I need anything, who am I going to call?” Suzan has always written her thoughts in the diary she has carried with her for the last decade. She safeguards it closely. Aside from protecting her privacy, she doesn’t want it to get damaged. Her best friend wrote in it too. She passed away this year, so the diary means even more now.

Suzan spends a lot of time at the East End beach in Portland. “The smell of the ocean brings me to a different place.” Although water is one of Maine’s great resources, daily life for most people in Maine is not largely affected by the rain. Suzan says it doesn’t rain much here, but it brings back vivid childhood memories of playing outside in the mud in Sudan. “The struggle of getting the water out of the house, I still remember.” Recently, she was able to visit Sudan. It rained so hard while she was there, that she longed to play in the mud again like she did as a child. It was an emotional trip for her, and hard. “I went back and finally met with so many people that would be a great addition to my life.” It moved Suzan profoundly that people with so little could be so happy with what little they have. Sudan will likely never be home again, but it is an intrinsic part of her that she carries with her in Maine.

Community engagements and exhibitions."Carried From Home", current exhibit, Catholic Charities Maine, Lewiston, Maine.

"Carried From Home", Immigration Welcome Center, Portland Maine.

"Carried from Home", September 2018,City Hall, Portland, Maine 2019.

"Carried From Home" , Venn + Maker, June 2018, Portland, Maine.